Ah, Switzerland. Land of fondue, chocolate, and neutrality. If you want to learn more about this unique little country, maps are a great way to start. Not only does Switzerland have fascinating geography, but it also has a long and storied tradition of cartography and design.

1. Where in the world?

But you already knew that, right? And you also knew that the capital is Bern, not Zurich or Geneva. Switzerland is not very big. It’s the world’s 135th largest country. Four U.S. counties are larger. But what it lacks in size it makes up in other ways. For example, The Economist ranked it the best country in the world to be born in.

2. Confoederatio Helvetica

Switzerland is made up of 26 cantons, many of which were established as sovereign states hundreds of years ago. Then, in 1848, with the establishment of the Swiss Constitution, the cantons joined together to form the Swiss Confederation, or in Latin, Confoederatio Helvetica. That’s where the abbreviation “CH” comes from.

Switzerland is a federal states and the cantons still retain strong identities and policy autonomy, in a way that’s analogous to the states in the U.S.

3. A multilingual nation

Switzerland has four official languages: German (the most prevalent), French, Italian, and Romansh. Romansh is spoken by less than 1% of the population, and only in a few places in Eastern Switzerland. I personally have never heard an utterance of Romansh. But it’s the only language unique to Switzerland, so I suppose it has a special place in the Swiss national identity.

The Swiss have a well-deserved reputation as polyglots. Almost all Swiss people I know speak at least two Swiss languages plus English, and some many more.

4. Let’s get physical

This map shows the terrain of Switzerland together with land use. You can immediately see that Switzerland is a mountainous country, with the Alps dominating the southern 2/3 and the smaller Jura Mountains along the northwest border. The bit in the middle, which is also where most of the people live, and most of the agricultural land and industrial production are located, is called the Swiss Plateau.

You’ll also notice the lakes. Switzerland has a lot of them, including some of the biggest lakes in Europe. Most Swiss lakes, including Geneva, were formed when the ice sheets of the last glacial period retreated, leaving deep basins carved by ice, and filling with water from the melting glaciers. More on the ice age below.

5. A geologist’s paradise

Ok, this one’s not a map. It’s a geologic cross section (source) showing a very simplified version of what the earth might look like if you cut out a slice 50 km deep and several hundred km long from Italy in the south, through the heart of the Swiss Alps, and north into France. The diagram gives an idea of the folding and faulting wrought by the massive tectonic collision that created the Alps.

In simplest terms, the Alps formed when two tectonic plates, the African and Eurasian plates, collided over millions of years. It all started in the Late Cretaceous, around 100 million years ago, when the ocean that separated what are now Eurasia and Africa began to close. Eventually the two continental masses themselves collided, with rocks on African side thrust up and over the Eurasian plate. The suture where the two plates became fused is called the Insubric Line.

The Alps are tectonically active to this day, raising up on the order of 1 mm per year. To geologists, the Alps are special because they were the first collisional mountain range to be studied extensively and much of the early understanding of structural geology comes from those pioneering Alpine studies.

6. The ice age

If the great tectonic collision provided the medium of folded, faulted and uplifting rock, the ice ages were the sculptor who fashioned the Swiss Alpine landscape into the wonder that we recognize today. The map above shows the extent of the ice cap that covered much of present-day Switzerland during the last glacial maximum, about 20,000 years ago.

The glaciers carved the spectacular U-shaped valleys and jagged peaks of the Alps. They also created the basins that would eventually be filled with water and form the Swiss lakes. Other evidence of the the glaciers is often visible in Switzerland, such as great boulders carried by the ice and stranded, and gentle hilly moraines that dot the Swiss Plateau.

7. The trains run on time

Back to the present day. One of the best things about Switzerland is the passenger train network, depicted on the map above, which you’ll find in every train car and station in the country. It’s the densest passenger network in Europe. You really can get just about anywhere on the train, even high into mountain villages on the many cog wheel and narrow gauge lines. And the trains are on time. Well, 95% of them, according to the Swiss national railway company. To really appreciate the attention to detail that the Swiss give to rail travel, check out this incredible diagram.

8. Let’s hit the slopes

When you think of Switzerland, you think of skiing, and the Swiss Alps have some of the top ski resorts in the world. One thing I love about the alpine ski resorts, aside from the great slopes, are the beautiful hand drawn piste maps. Here’s one of the Grindlewald/Wengen area in the Bernese Oberland. Just looking at it makes me want to start planning next year’s ski trip.

9. Direct democracy

“Anti-Einwanderungsinitiative 2014” by Furfur, based on the file Kantone der Schweiz.svg, made by KarzA. – Own work, data source: Neue Zürcher Zeitung: SVP-Abstimmungskrimi vorbei: Die Überraschung ist perfekt. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Switzerland is famous for its direct democracy, the process whereby voters frequently weigh in on referendums, popular initiatives, and even have veto power over laws. The Swiss vote a lot. Elections happen about four times a year and often contain several referendums at the national, cantonal, and local level, as well as ballots for elected representatives.

The map above shows the results of a popular initiative in 2014 that sought to restrict immigration by EU nationals into Switzerland. It passed narrowly, with strong support from the Italian- and German-speaking regions and despite opposition in the French-speaking regions.

Immigration is a contentious issue in Switzerland (as in many other parts of the world). Relative to its population, immigration levels are quite high, compared to say, Germany or even the U.S. In some cases, xenophobia wins out in popular initiatives, such as when the Swiss voted in 2009 to prohibit the construction of minarets.

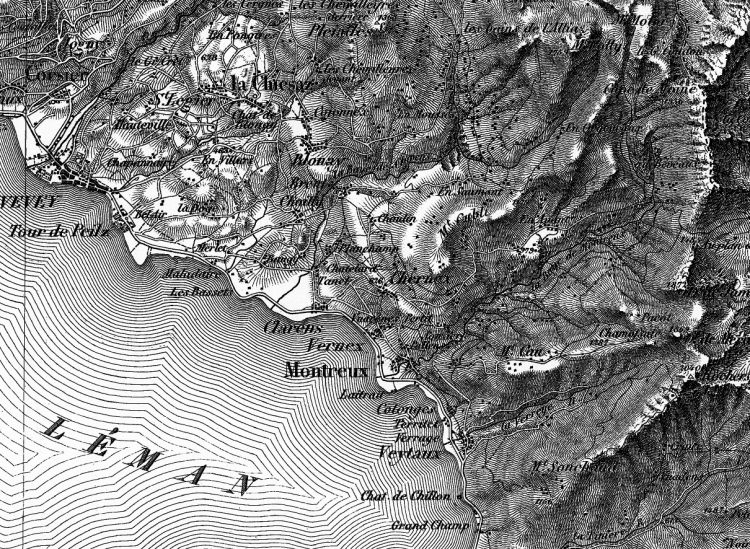

10. A rich cartographic history

With its varied geography and strong scientific and educational traditions, it’s no surprise that Switzerland has produced some stunning cartography. The first official map series to encompass all of Switzerland was produced by Guillaume-Henri Dufour and published from 1845-1865. The result of decades of surveying, drawing, copperplate engraving, and printing, the map achieved a high level of accuracy and detail for its time, and is also distinguished by the attractive use shading to show topography. More information on the Dufour map, as well as the equally impressive Siegfried map is available here.

Swiss excellence in mapping continues to this day. For example, the Federal Geoportal has a great mapping tool that allows you to access and display hundreds of data layers, from road networks to wetlands.