It’s been quite some time since my last post. I have been busy with a young child, new job, and an international move. But I’m hoping to get back into posting and making visualizations on a regular basis.

The reason for this post is that I came across an interesting resource called the International Environmental Agreements Database Project, hosted at the University of Oregon. The database contains information on about 1100 multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs) dating back to 1857. The data include the title, type (an original agreement or a protocol or amendment to an existing agreement), dates of signature and entry into force, and the parties. For some agreements there is even data on performance as well as coding to allow for comparison of the actual legal components.

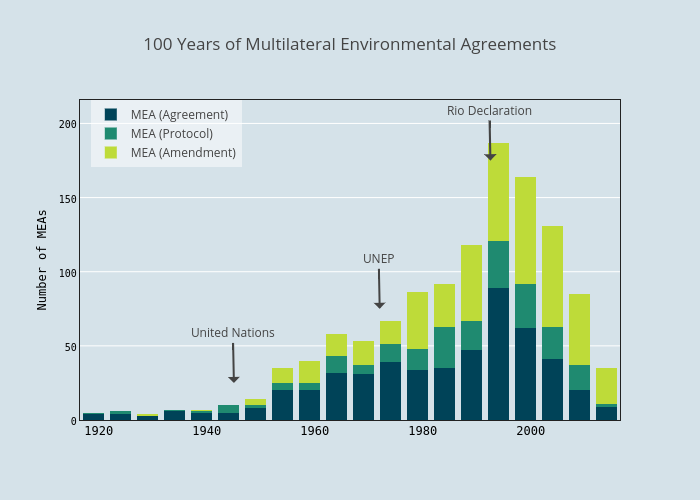

As an initial exploration, I simply looked at how many agreements were concluded over time. The plot below shows the results for the last 100 years. Click for the interactive and shareable plot.ly version.

There is a pretty interesting pattern. From the early 20th century until the 1950s there are not that many MEAs. Then the pace picks up in mid-century, peaking in the early 1990s, and declining considerably after that.

What’s going on? Have all the easy agreements been reached and there is nothing more for countries to negotiate about? Maybe that’s part of it, but I think it has something to do with an event that coincided with the peak in MEAs – The 1992 Earth Summit and the resulting Rio Declaration on Environment and Development.

The Earth Summit was a huge event in the global environmental community, and occurred at a high point of optimism about multilateralism. There was a flurry of MEA activity around this time. But there was also a building movement to ensure that international environmental diplomacy was benefiting the poor, and in particular, developing countries.

The Rio Declaration enshrined the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities. This is the idea that while all nations have a responsibility to protect the global environment, rich nations should shoulder a greater share of the burden.

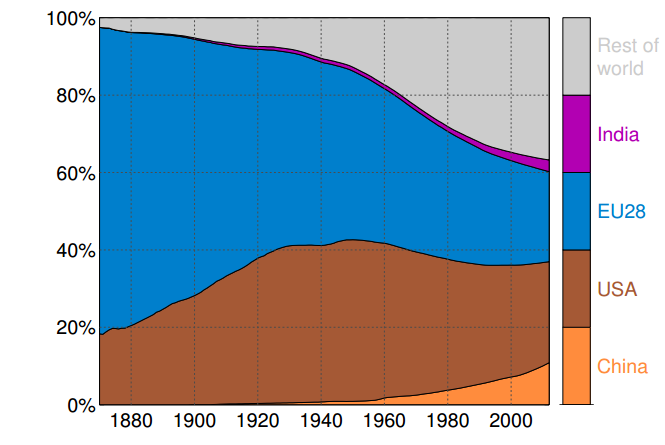

It is a noble sentiment, and one that in my view makes a lot of sense. But it had the effect of making it more difficult to reach agreements in international environmental negotiations. Developing countries started going into the negotiations expecting more support, in the form of funding, reduced obligations, or technology transfer, from the developed world. Common but differentiated responsibilities is at the root of a major sticking point in global climate talks. Should China, India, and other rapidly developing nations have the same stringent obligations as more mature economies?

I certainly don’t think this is the only cause of the decline in new MEAs in the last 20 years. And neither can I claim to be the first to think about the Rio Declaration’s impact on MEAs. There’s an entire literature on it. For example, Richard Benedick discussed this theme at length in reference to the Montreal Protocol and its aftermath in his book Ozone Diplomacy.

As a final disclaimer, for this analysis it would be best to filter the IEA database to exclude those MEAs that only have a few parties. That way you could really focus on the rate of global or large regional MEAs over time. Perhaps I’ll do that next.

But in any case, it’s an interesting dataset and an interesting pattern. And a good excuse to step back and think about the big picture in global environmental politics.